Bonus Ep / What does an ecologist eat in the age of climate change?

A bonus episode with foodie scientist Mark J. Easter's uses science to illustrate why changing what we eat is not just a matter of science.

My initial foray into podcasting was an effort called You Can’t Eat Money.

Inspired by a quote from Alanis Obomsawin, people loved the name You Can’t Eat Money and it made sense as a starting point. Food was my own way into understanding climate change and my relationship with the more-than-human world. I wanted to share my passion and what I learned with others.

"When the last tree is cut, the last fish is caught, and the last river is polluted; when to breathe the air is sickening, you will realize, too late, that wealth is not in bank accounts and that you can’t eat money." - Alanis Obomsawin

On You Can’t Eat Money, I got to talk to some of my culinary heroes. Chef Dan Barber - of Blue Hill and Chef’s Table fame - and I talked about how a more sustainable version of our food system is also a more delicious one. Ben Aguilar of The Berry Center and I nerded out on Wendell Berry’s beautiful philosophy and writing.

It was dreamy and a great way to cut my teeth in the world of podcasting. So even though I decided to open the aperture in my exploration of our relationship with nature and the more-than-human world through Ecosystem Member, food is still my home base and a home base for many others.

It’s easy to see why.

The world is full of delicious food and as a privileged eater in the Global North, I have options in abundance and choices to make. When I lived in London, I fell in love with Sri Lankan food (pictured). In New York, fantastic Thai food from Pok Pok and ramen were new discoveries for a kid from a small suburb in Texas. In Los Angeles, I lived down the street from the Venice Farmers Market and the LA Funghi stand introduced me to mushrooms I had never heard of before.

To make it abundantly clear, for most of my life I haven’t really used any guide to eating other than how absolutely fucking delicious something was when I was hungry.

When I lived in New York and started to read about the environmental impact of our food choices, I started to make changes in small steps. I was never really a big beef eater, so that was pretty easy to cut. I was also the rare person who never really cared for bacon, so pork followed beef off my plate. Living in Brooklyn, I had more than enough options to replace them from some of the world’s best restaurants.

I didn’t really have a clear end in mind, I just made changes as I learned more about the impact of certain parts of our food system on nature and the more-than-human world. The shift was fairly seamless. The only hiccup coming when I told my family in advance that I wouldn’t be eating the Thanksgiving turkey and they assumed I was joking and tried to serve me some anyway.

As I dug into food more through You Can’t Eat Money, I came to uncover what were often emotional relationships people had with good. And it has made me hesitant to become prescriptive.

“Food becomes the organizing principle for the relationships that give us strength.”

“The Blue Plate” by Mark J. Easter

Rather than tell readers and listeners what to eat, I tried to let my guests provide their stories and data, and let people make a decision for themselves. Even when I shared the science, I did it through the lens of my personal journey and my own relationships.

That’s why I am re-releasing an episode from the You Can’t Eat Money feed here on Ecosystem Member. Mark J. Easter’s recent book The Blue Plate - published by Patagonia’s book arm - finally brought the science and cultural lenses together to examine our food system. Rightfully, it was just nominated for an award from the James Beard Foundation.

Easter - a retired ecologist with more than 50 scientific papers and reports about land use to his name - deftly brings together the ingredients of rational and emotional to help readers understand the impact of their food choices. And even for someone very interested in the food system, I learned a lot.

Let’s dig in!

Local Food is About More than Food Miles

One of my favorite parts of The Blue Plate is Mark’s visits with his colleague Amy to a local farm CSA (an idea originally conceived by Black horticulturist Dr. Booker Whatley as Mark notes) called Sunspot Urban Farm.

Mark is quick to point out that most food grown in the United States travels for at least a thousand miles over several days. More perishable food like fish can even travel cross-country by emissions-intense airplane. A CSA can reduce those miles to just a tenth to a fifth of industrialized food system miles.

Yet Food Miles are not the only reason to join a community supported agriculture program.

As past You Can’t Eat Money guests mentioned, a CSA can help you connect with the people who grow your food while sharing the risk of food production. With a CSA, you’ll also quickly learn about the food seasons of your area and support smaller farms like Sunspot that can experiment with new, lower impact methods of growing (more on that in The Blue Plate).

The Modern Food System Has Disconnected Us from Place and Season

In the book, Mark visits vegetable growers in the Lower Colorado River Basin.

“More than 90% of fresh vegetables eaten during the winter in the United States are grown in the region downstream of where I floated, irrigated with waters diverted from the Colorado River.”

That’s pretty incredible not just because of the transport required but also the fact that the Colorado River is over-allocated. That means that more water from the Colorado is assigned to people with claims for things like irrigation to grow food than actually exists. And a huge chunk of the food we eat relies on that over-allocated source.

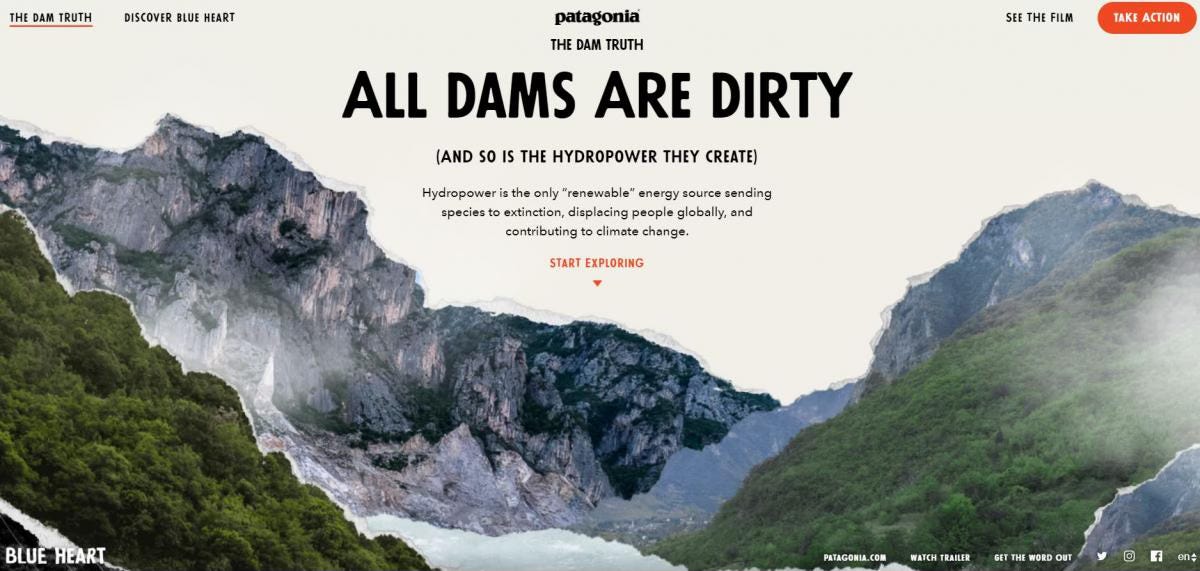

The water is being delivered through a reliance on dams, which come with a whole host of environmental challenges as Mark shares in the book. These dams not only control the flow of the Colorado (and the lives of the fish in it), they also enable us to eat vegetables we like regardless of season and wherever we live, even if is a desert location like Las Vegas and Phoenix. Plus, the energy hydroelectric dams deliver has a carbon footprint equal or greater to than any other fossil fuel source of energy.

Fossil Fuels also play a role in this disconnection.

“…fossil fuel use shifts what is known as the “energy balance” in agriculture so that far more fossil fuel calories of energy are burned to grow a crop compared with the caloric energy of the harvested crops.”

When we can get the ingredients we want throughout the year using more energy intense methods and get energy-hungry air conditioning and clean water to the middle of a desert, we lose our connection to the land. And we lose the opportunity to see the warning signs it is sending us in our own gardens.

We Need to Make Friends with the Microbes

Mark’s dedication page simply reads, “For the microbes.”

Throughout The Blue Plate, Mark brings to life how microbes play a key role in our food system. From the gut of ruminants like cows and goats to the manure lagoons from animal agriculture and the compost piles of our food waste, microbes drive the food system.

Why are microbes important?

“All terrestrial life begins with soil; however all soil was rock before plants and microbes biochemically transformed rock.”

As Mark goes on to explain, microbes combine with fungi to create dense root hairs. These root hairs gather and shuttle water to plants. The plants then “weep” mucus- like exudates that feed the soil. A beautiful cycle.

Microbes also play a key role in not just breaking down organic matter in the soil, but actually forming carbon in the soil. (Of which the plow then unleashes from the soil. This led to “one of the greatest pulses of carbon emissions” with the introduction of agriculture in the Great Plains as Mark points out.)

Microbes play a slightly different role in animal agriculture.

Ruminants like cows, goat and sheep can’t digest grass directly, but they have evolved a symbiotic relationship with microbes in their gut that can. The microbes however quickly grab all of the oxygen that enters a ruminant’s stomach. Without oxygen, the ruminant releases methane rather than the less intense carbon dioxide that humans, pigs and chickens release. The manure from these animals can contribute even more methane when added to a pooled lagoon.

Yet, microbes also play a positive role in beneficial composting.

Food waste is a huge issue, especially in the United States. Around 30 to 40% of our food is wasted. And it isn’t just vegetables.

“…about a third of meat is never consumed but goes into landfills”

When these food products go into a landfill, the microbes quickly consume the oxygen and what’s left creates massive amount of emissions.

“…if the emissions from all the food dumped into landfills were its own country, it would have the third largest greenhouse gas emissions of all the world’s countries.”

But, if the US goes “all-in” on a well-managed composing system that allows the microbes to break down organic matter like in South Korea (details in the book), we could, “effectively cut the total emissions coming from our food systems by somewhere between a third and a half…We just have to feed the microbes in the right places and avoid feeding them in the wrong places.”

Regenerative Farming Practices Are Only Part of the Solution

We talked a lot about regenerative farming practices on the You Can’t Eat Money podcast.

From cover crops that can replace chemicals by controlling weeds biologically to eliminating plowing and tilling to keep carbon in the soil, regenerative farming can support, “healthier, more productive crops and higher yields,” while increasing soil and plant resilience during droughts.

When combined with animal grazing - which help return nitrogen back to the soil through animal urine and manure - regenerative farming practices with cover crops can have a positive climate impact, even if it has become a little overhyped.

“An optimistic story has emerged that grazing livestock can lead to more carbon in the soil. In some cases that is true, but not necessarily everywhere, and the increase in soil carbon does not continue forever.”

The fact that regenerative practices are overhyped doesn’t mean they don’t have any positive impact.

“The best we appear likely to achieve through these farming practices, however, is to offset between one-sixth and one-third of today’s annual worldwide carbon footprint, if low-carbon farming practices were widely adopted over the next three decades.”

We Need to Consume Less Meat and Dairy

“Raising meat - and especially meat from cattle, sheep and goats - creates more emissions by a factor of between ten and fifty than any other food source except shrimp farmed in clear-cut mangrove forests.”

“When scientists compare the nutrition in milk with the nutrition in other animal-based foots, milk’s carbon footprint on a per-calorie or per-gram-of-protein basis is second only to beef, lamb, and goat meat, and greater than pork and chicken meat.”

While this isn’t new news, the science that Mark presents is strikingly clear. And yet, because this has become as much a cultural conversation as a scientific one, it has created a veil of confusion. (Here’s more detail on the misleading McDonald’s-backed study I mention in the intro of this episode.)

More than 95% of meat eaten in the United States comes through a CAFO (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation), one of those giant, densely crammed lots you see on the side of Interstate 5 in California. And according to Dr. Pete Smith at the University of Aberdeen, who Mark spoke with for the book, grazed alternatives are not an option at the rate we consume beef - “I don’t think this method of production would support the numbers of livestock currently produced. So it is a bandage on the problem rather than a cure.”

Even when it comes to trials to introduce chemicals to alter the microbes of the gut of ruminants to reduce methane emissions, the expert Mark speaks with believes, “we are years to decades away from having a chemical that might be practical.” And we don’t even know if, “ruminants can tolerate these additives in their stomachs over time.” (The Bezos Earth Fund is funding research in this area.)

How we feed the animals in our agricultural systems also presents an issue.

“Demand for soybeans to feed pigs in Europe and elsewhere is driving deforestation in the Amazon and other parts of the world.”

So is there any way to responsibly - from a climate change perspective - raise animals for human consumption?

Mark writes that there are two strategies we need to leverage to meet human demand for food while stabilizing the climate.

The first is integrating livestock into croplands that are used to raise food for humans. This is a key feature of regenerative systems, although as Mark points out, experts don’t believe grazing (as opposed to CAFOs) can support the same amount of animals on the same size plot of land.

The second is to raise livestock for human consumption only on the “ecological leftovers”. This directly means no more deforestation to support animal grazing or growing food for animal feed, keeping some of our best carbon sinks intact. It would also mean that the scale of animal agriculture is significantly reduced, while leaving it as an option for places where it is, “the only type of sustainable agriculture.”

Where does that leave us?

“At a time when we are told that time matters, when every little bit helps, when every single pound of methane avoided is a pound of cure, it feels like so much is being demanded of us when our leaders are making such poor choices about our future, and so little is being done in other sectors that increasingly matter. Why should I change what I eat or be bothered with how my food is produced, since relatively little seems to be done elsewhere?”

The above passage from Mark comes toward the end of The Blue Plate, yet explains as much as all of the facts in the book do about why changing what we eat is really hard.

In a busy world where most people are not engaged on this issue, why should I change?

My theory - and based on the book and podcast I think Mark agrees - is that we’ve become so disconnected from our food system that we no longer see growing food as a community activity like he engages in with Sunspot and community composting.

Many of us tend to shop at large grocery stores with tens of thousands of pre-packaged products. We don’t ever meet those who grow our food. We don’t see what happens to their family and their farm when an extreme weather event driven by climate change occurs. ($21B from crop losses in 2023 and just over $20B in 2024.) We don’t understand the ramifications of grocery store chains driving down the price they pay farmers for products.

All of the amazing solutions Mark shares in the book will need to be implemented to reduce the impact of our food system on the Earth’s systems and gifts. And as Mark writes, these tactics are already making progress in reducing impact.

But this isn’t just a matter of the head, it’s a matter of the heart.

“Farming by the measure of nature, which is to say the nature of the particular place, means that farmers must tend farms that they know and love, farms small enough to know and love, using tools and methods that they know and love, in the company of neighbors that they know and love.”

Bringing it to the Table: Writings on Farming and Food by Wendell Berry

Order your copy of The Blue Plate today.

Watch/Listen to the Episode