Can we imagine a world beyond sustainability?

Yes we can. And art, imagination and creativity can help us get there.

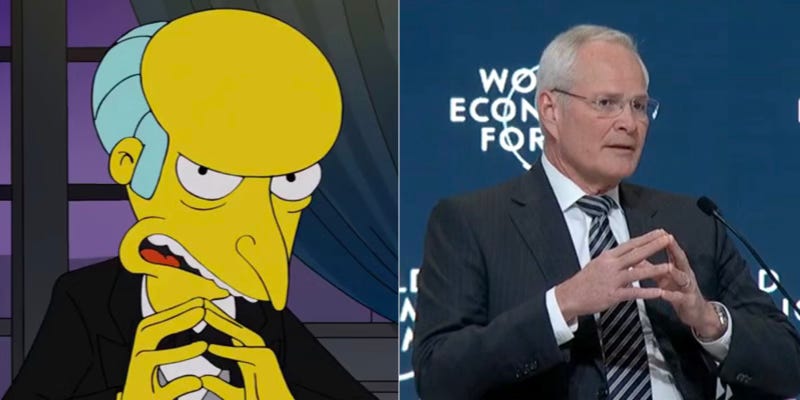

Darren Woods is the CEO of ExxonMobil, the largest U.S.-based oil and gas company and largest investor-owned oil and gas company in the world.

On Bloomberg’s Zero podcast from COP29, Woods said "What the world needs is a [energy] transition that companies can make money in and generate returns on.” And to think I thought we needed to transition our energy system to have a healthy, habitable planet for all living beings. Silly.

To be clear, Woods doesn’t mean investing in a transition to renewable energy. ExxonMobil is explicit that it is focused on reducing the emissions from its existing business. This makes his apparent comment to the Financial Times in 2023 that ExxonMobil doesn’t see any viable alternatives to fossil fuels make a lot more sense, despite many world leaders saying the transition to clean, renewable energy is inevitable.

Woods’ point of view is one of short-sighted self-preservation.

As the CEO of the largest investor-owned oil company in the world, Woods is responsible for making a profit to return money to shareholders either through increasing the value of the stock, paying dividends to shareholders, or holding a stock buyback. If the stock loses value because the future prospects of the company are seen as not favorable, Woods will be out of a job and his $36.9M in compensation (2023). He’s currently trying to squeeze the last ounce of juice out of the fossil fuel fruit through investment in unproven or questionably responsible ‘solutions’ like carbon capture and blue hydrogen.

All of this illuminates the vague definition of sustainability in ExxonMobil’s 2023 sustainability report:

That’s what sustainability means for us – managing our business in a way that creates value for our stakeholders, not just for the next quarter or the next year, but for the long run.

Many companies take ‘sustainability’ to mean the ability for the company to continue its business - and profits - as it currently is. They focus on an economic sustainability (often under the ‘green halo’ of the perception of term sustainability).

Others lump sustainability in with other social good initiatives. In this version, it is about prioritizing the well-being of people and the human communities they exist in.

And of course, there is environmental sustainability, which in the business world tends to focus on how a company uses the ‘natural resources’ (or ‘gifts’ as Robin Wall Kimmerer would call them), we get from the more-than-human world and the carbon emissions in its supply chain.

My hunch is that ExxonMobil isn’t integrating the latest thinking around non-human stakeholders, so it is primarily thinking of sustainability in the social and economic space. That is unless you consider not spilling your toxic product into the ocean as ‘creating value’ for the Earth.

The confusion around ‘sustainability’ created by companies like ExxonMobil reminds me of an essay Arne Naess wrote about Deep vs Shallow Ecology.

“The shallow ecology movement is concerned with fighting against pollution and resource depletion. Its central objective is the health and affluence of people in the developed countries.”

“The deep ecology movement has deeper concerns, which touch upon principles of diversity, complexity, autonomy, decentralization, symbiosis, egalitarianism and classlessness.”

Shallow ecology is about limiting damage to keep what we have.

Deep ecology is about imagining something better.

Right now, corporate sustainability - whichever definition you use - is a lot like shallow ecology. It’s aware of its place in the world and the harm a company is doing to that world, but unfortunately it isn’t really a powerful enough tool to make headway in most corporations. Thus, its focus is more on maintaining the status quo through small, acceptable change - or shifting the blame to us - than imagining something new. Is it any wonder that some of the leading programs for executives to learn about sustainability are at places like Harvard and Cambridge?

And this illuminates a big problem with sustainability as it currently exists - a lack of the imagination that is needed to create that new thing, not just band-aid a broken system.

As Buckminster Fuller said, “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete."

So how do we create a new, ecologically-connected reality?

This is where the arts comes in.

The literary arts, in particular science fiction, has a long track record of imagining a more ecologically-connected future. Take Octavia E. Butler’s Earthseed, a fictitious religion from the novel Parable of the Sower of which its central verse reads:

Consider: Whether you're a human being, an insect, a microbe, or a stone, this verse is true.

All that you touch

You Change.

All that you Change

Changes you.

The only lasting truth

Is Change.

God

Is Change.

Another great example is Kim Stanley Robinson’s “The Ministry for the Future”, which Beth Thoren cited as an ever-present resource in her episode of Ecosystem Member.

Robinson’s science fiction book is speculative, helping the reader imagine the future of a world ravaged by the climate crisis. Smartypants Ezra Klein went as far to say “If I could get policymakers, and citizens, everywhere to read just one book this year, it would be Kim Stanley Robinson’s ‘The Ministry for the Future’.”

Outside of the written word, artist David Blandy took his science fiction board game ‘Alien Pastoral: The Strain’ to the recent COP16 biodiversity conference in Colombia.

In ‘Alien Pastoral’, participants in the role-playing game explore “the strange and often blurred spaces between agriculture, technology and capitalism” to “design a research station together, with seedbeds, orchards and laboratories.”

Yes, using these artistic works as tools in the boardroom rather than just as entertainment is probably going to make some chief financial officers uncomfortable, but would it be any more uncomfortable than explaining a loss of a third of your projected financial growth?

If you are reading this newsletter, you’ve probably heard of Solarpunk. It is a counterculture, Internet-based art movement that emerged in 2008 that imagines collectivist, ecological utopias powered by clean energy. But have you heard of soilpunk?

A few weeks ago, I came across a new initiative from a ‘planet-first’ beverage company called Tractor to launch a soil-based climate fiction zine called Tractor Beam “to explore bold, optimistic futures where regenerative farming and soil science inspire how we live and thrive on this planet.” (You can actually submit a piece to be considered for inclusion right now, with a deadline of November 22.)

I don’t know if the company plans to use the material in its annual planning process, but I admire its embrace of imagination.

As Timothy Morton wrote in his essay “And You May Find Yourself Living in an Age of Mass Extinction”, we currently exist in something like a ‘control society’ (a term coined by philosopher Gilles Deleuze). This control society is about driving efficiency and authority. If we want to be ecological, our society must give up that control and be “a bit haphazard, broken, lame, twisted, ironic, silly, sad.” We must have “seduction and repulsion rather than authority.”

While jarring at first read, I think Morton is directionally right. The world, including the non-human natural world, is not always predictable and formulaic as we might like to think. And companies could benefit from adding some messiness to their approach.

Rather than authoritatively beating people over the head with sustainability facts and figures, causing guilt, shame and inaction, we need to think ecologically. We need to seduce people into imagining something better and become repulsed by the lack of imagination of people like Darren Woods.